- Home

- Jane Austen

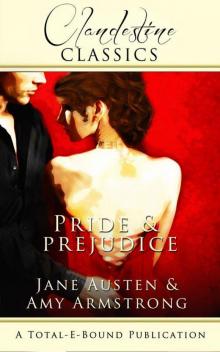

Pride and Prejudice (Clandestine Classics)

Pride and Prejudice (Clandestine Classics) Read online

A Total-E-Bound Publication

www.total-e-bound.com

Pride and Prejudice

ISBN #978-1-78184-077-1

©Copyright Amy Armstrong 2012

Cover Art by Posh Gosh ©Copyright July 2012

Edited by Eleanor Boyall

Total-E-Bound Publishing

This is a work of fiction. All characters, places and events are from the author’s imagination and should not be confused with fact. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead, events or places is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form, whether by printing, photocopying, scanning or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher, Total-E-Bound Publishing.

Applications should be addressed in the first instance, in writing, to Total-E-Bound Publishing. Unauthorised or restricted acts in relation to this publication may result in civil proceedings and/or criminal prosecution.

The author and illustrator have asserted their respective rights under the Copyright Designs and Patents Acts 1988 (as amended) to be identified as the author of this book and illustrator of the artwork.

Published in 2012 by Total-E-Bound Publishing, Think Tank, Ruston Way, Lincoln, LN6 7FL, United Kingdom.

Warning:

This book contains sexually explicit content which is only suitable for mature readers. This story has a heat rating of Total-e-sizzling and a sexometer of 1.

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE

A Clandestine Classic

Jane Austen & Amy Armstrong

Dedication

I dedicate this book to everyone looking for their own Mr Darcy and those who are lucky enough to have already found him. Dad, I love you. Mam, I miss you every day. For Claire Mc, thank you for being a wonderful friend.

Chapter One

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

“My dear Mr Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

As Mrs Bennet’s shrill voice carried through to the sitting room, Elizabeth Bennet’s hand hovered over the handkerchief she had been embroidering, the delicate stitching long forgotten. Unlike her sisters, Elizabeth did not like to eavesdrop, but the volume of her mother’s voice was so high, it could hardly be avoided.

Mr Bennet replied that he had not, in fact, heard the news.

“But it is,” returned she, “for Mrs Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England, that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr Morris immediately, that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Elizabeth was intrigued by news of Netherfield’s new owner and hoped to discover more about him. Country life offered few distractions and so newcomers were unquestionably opportune. Her sisters would be beside themselves.

“What is his name?” enquired Mr Bennet.

“Bingley.”

“Is he married or single?”

Leaning forward in her chair, Elizabeth eagerly awaited her mother’s response.

“Oh! Single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune, four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!”

Elizabeth smiled to herself. It was a fine thing indeed. She was well acquainted with the single men who lived in their small but pretty part of the countryside in Hertfordshire and most of them were insufferable bores. Elizabeth had hopes that Mr Bingley would be different.

“How so? How can it affect them?” enquired Elizabeth’s father.

“My dear Mr Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.”

If Mr Bingley did choose to marry, it would not be to Elizabeth Bennet, for she had no desire to take a husband—even though she had often wondered what it would feel like to have a man’s hands caressing her body, his breath hot on her neck. Her heart began to beat thunderously as she imagined her skirts lifted, and firm, confident fingers gliding over her heated flesh, moving higher until they found her most private of places. She thought of them stroking gently, then with more fervour, until she cried out from a release she could only begin to imagine. Elizabeth was quite sure her illicit thoughts had no place in the mind of a lady, but though she tried often to control them, she was never very successful.

“Is that his design in settling here?” asked Mr Bennet, drawing Elizabeth’s attention back to the conversation in the other room.

“Design! Nonsense, how can you talk so!” exclaimed Mrs Bennet. “But it is very likely that he may fall in love with one of them, and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.”

Upon entering the room, Elizabeth’s sister Jane asked, “Lizzie, what ails you? You look flushed. Are you unwell?”

“I am quite well, sister,” said Elizabeth. “It is…hot in here. Is it not?”

Jane Bennet regarded Elizabeth curiously. “I had not noticed.” Elizabeth and Jane quieted when their father next spoke.

“I see no occasion for that,” said Mr Bennet to his lady. “You and the girls may go, or you may send them by themselves, which perhaps will be still better, for as you are as handsome as any of them, Mr Bingley may like you the best of the party.”

“My dear, you flatter me. I certainly have had my share of beauty, but I do not pretend to be anything extraordinary now. When a woman has five grown-up daughters, she ought to give over thinking of her own beauty.”

“In such cases, a woman has not often much beauty to think of.”

“But, my dear, you must indeed go and see Mr Bingley when he comes into the neighbourhood.”

“What are they talking about?” Jane Bennet whispered to her sister. “Who is Mr Bingley?”

“The new tenant of Netherfield Hall,” said Elizabeth.

Curiosity piqued, Jane took the seat next to her sister, and joined her in listening to their parents’ exchange.

“It is more than I engage for, I assure you,” said Mr Bennet.

“But consider your daughters,” implored Mrs Bennet, her volume increasing with each word she spoke. “Only think what an establishment it would be for one of them. Sir William and Lady Lucas are determined to go, merely on that account, for in general, you know, they visit no newcomers. Indeed you must go, for it will be impossible for us to visit him if you do not.”

“You are over-scrupulous, surely. I dare say Mr Bingley will be very glad to see you, and I will send a few lines by you to assure him of my hearty consent to his marrying whichever he chooses of the girls, though I must throw in a good word for my little Lizzy.”

Jane Bennet inhaled a sharp breath, and her hand lifted to cover her mouth, but Elizabeth merely chuckled. She was well versed in her father’s humour, which was much like her own.

“I desire you will do no such thin

g,” Mrs Bennet returned. “Lizzy is not a bit better than the others, and I am sure she is not half so handsome as Jane, nor half so good-humoured as Lydia. But you are always giving her the preference.”

“They have none of them much to recommend them,” replied he, “they are all silly and ignorant like other girls, but Lizzy has something more of quickness than her sisters.”

“Mr Bennet, how can you abuse your own children in such a way? You take delight in vexing me. You have no compassion for my poor nerves.”

“It is a wonder she has any nerves left,” remarked Elizabeth to her sister.

“You mistake me, my dear,” said Mr Bennet. “I have a high respect for your nerves. They are my old friends. I have heard you mention them with consideration these last twenty years at least.”

“Ah, you do not know what I suffer.”

“But I hope you will get over it, and live to see many young men of four thousand a year come into the neighbourhood.”

“Four thousand?” enquired Jane, her eyes wide with surprise.

Elizabeth smiled mischievously at her sister. “If that is what mamma says, then it has to be true.”

“Do you think he will be handsome?”

Elizabeth averted her eyes from her sister’s inquisitive gaze. “I had not thought on the matter.”

“It will be no use to us, if twenty such should come, since you will not visit them,” said Mrs Bennet regretfully.

“Depend upon it, my dear, that when there are twenty, I will visit them all.”

Elizabeth and Jane shared in their father’s joke. Mrs Bennet made no reply.

Mr Bennet was so odd a mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humour, reserve, and caprice, that the experience of three-and-twenty years had been insufficient to make his wife understand his character. Her mind was less difficult to develop. She was a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper. When she was discontented, she fancied herself nervous. The business of her life was to get her daughters married, its solace was visiting and news.

When Elizabeth Bennet’s sisters Lydia and Mary entered the sitting room, Elizabeth returned to her embroidery, leaving them to speculate about Mr Bingley. It was decided by Lydia that he would indeed be handsome, and Jane wished that he were kind. Mary thought them all puerile. Although Elizabeth endeavoured to forget about her earlier fancies, she added that she hoped Mr Bingley would have a sharp mind and one that would stimulate her. Though when her own mind betrayed her, producing images of the way her body could be stimulated, she felt heat return to her cheeks and tried to hide the blush from her sisters. They were silly notions anyway. Elizabeth would never act upon her deepest desires. To do so would surely ruin her.

Chapter Two

Mr Bennet was among the earliest of those who waited on Mr Bingley. He had always intended to visit him, though to the last always assuring his wife that he should not go, and till the evening after the visit was paid she had no knowledge of it. It was then disclosed in the following manner. Observing his second daughter employed in trimming a hat, he suddenly addressed her with, “I hope Mr Bingley will like it, Lizzy.” Mr Bennet shared a knowing smile with his daughter Elizabeth, whom he had already informed of his earlier visit.

“We are not in a way to know what Mr Bingley likes,” said her mother resentfully, “since we are not to visit.”

“But you forget, mamma,” said Elizabeth, playing along with her father’s joke, “that we shall meet him at the assemblies, and that Mrs Long promised to introduce him.”

“I do not believe Mrs Long will do any such thing. She has two nieces of her own. She is a selfish, hypocritical woman, and I have no opinion of her.”

“No more have I,” said Mr Bennet, “and I am glad to find that you do not depend on her serving you.”

Elizabeth shook her head, amused by her father’s subterfuge—pleased he thought well enough of her to confide his secret. Hence, she had spent the entire day wondering about Mr Bingley, her thoughts often straying to places that were improper for a lady.

Mrs Bennet deigned not to make any reply, but, unable to contain herself, began scolding one of her daughters.

“Don’t keep coughing so, Kitty, for Heaven’s sake! Have a little compassion on my nerves. You tear them to pieces.”

“Kitty has no discretion in her coughs,” said her father, “she times them ill.”

“I do not cough for my own amusement,” replied Kitty fretfully. “When is your next ball to be, Lizzy?”

“Tomorrow fortnight,” said Elizabeth. She wondered if Mr Bingley would attend and hoped that it were so.

“Aye, so it is,” cried her mother, “and Mrs Long does not come back till the day before, so it will be impossible for her to introduce him, for she will not know him herself.”

“Then, my dear, you may have the advantage of your friend, and introduce Mr Bingley to her.”

“Impossible, Mr Bennet, impossible, when I am not acquainted with him myself. How can you be so teasing?”

“I honour your circumspection. A fortnight’s acquaintance is certainly very little. One cannot know what a man really is by the end of a fortnight. But if we do not venture somebody else will, and after all, Mrs Long and her daughters must stand their chance, and, therefore, as she will think it an act of kindness, if you decline the office, I will take it on myself.”

When the girls stared at their father eagerly, Elizabeth delighted at being in on the secret. Mrs Bennet said only, “Nonsense, nonsense!”

“What can be the meaning of that emphatic exclamation?” cried he. “Do you consider the forms of introduction, and the stress that is laid on them, as nonsense? I cannot quite agree with you there. What say you, Mary? For you are a young lady of deep reflection, I know, and read great books and make extracts.”

Elizabeth was quite certain that Mary wished to say something sensible, but knew not how.

“While Mary is adjusting her ideas,” he continued, “let us return to Mr Bingley.”

“I am sick of Mr Bingley,” cried his wife.

Elizabeth looked to her father, beseeching him with her eyes to end his pretence and put her mother and sisters out of their misery.

“I am sorry to hear that, but why did not you tell me that before? If I had known as much this morning I certainly would not have called on him. It is very unlucky, but as I have actually paid the visit, we cannot escape the acquaintance now.”

The astonishment of the ladies was just what he wished, that of Mrs Bennet perhaps surpassing the rest, though, when the first tumult of joy was over, she began to declare that it was what she had expected all the while.

“How good it was in you, my dear Mr Bennet! But I knew I should persuade you at last. I was sure you loved your girls too well to neglect such an acquaintance. Well, how pleased I am and it is such a good joke, too, that you should have gone this morning and never said a word about it till now.”

“Now, Kitty, you may cough as much as you choose,” said Mr Bennet, and, as he spoke, he left the room, fatigued with the raptures of his wife.

“What an excellent father you have, girls!” said she, when the door was shut. “I do not know how you will ever make him amends for his kindness, or me, either, for that matter. At our time of life it is not so pleasant, I can tell you, to be making new acquaintances every day, but for your sakes, we would do anything. Lydia, my love, though you are the youngest, I dare say Mr Bingley will dance with you at the next ball.”

“Oh!” said Lydia stoutly, “I am not afraid, for though I am the youngest, I’m the tallest.”

The rest of the evening was spent in conjecturing how soon he would return Mr Bennet’s visit, and determining when they should ask him to dinner.

The girls were filled with rapturous excitement and stayed up long past their usual bedtime to discuss the recent development. Elizabeth retired to her bedchamber early. With four sisters, she had little time to herself. Dressed in her nightgown, her long dark hair c

ombed out, she slid between the sheets of her bed and closed her eyes, letting her mind fill with the positively wicked thoughts she often denied herself.

A man—tall, rugged and infinitely handsome—trailing firm, wet kisses down her neck, his fingers whispering over her body like a hot summer’s breeze. His touch was gentle, but confident. He knew exactly what he was doing, and his proficiency excited her. His large hands skimmed over her breasts, finding the pink buds firm. He rolled them languidly between his fingers and the unfamiliar touch sent shivers of longing racing throughout her body. Then those hands moved lower…

Elizabeth quickly opened her eyes when she heard a noise out in the hall. She gasped, the beat of her heart sounding loud in her ears. The following silence did not assuage her fears and she chastised herself for being so careless and allowing her thoughts to endure. While the beating of her heart returned to its usual pace she waited for sleep to claim her. In slumber she could dream of all the things that in her waking hours, she was quite sure she would never be free to indulge in.

Chapter Three

Not all that Mrs Bennet, however, with the assistance of her five daughters, could ask on the subject, was sufficient to draw from her husband any satisfactory description of Mr Bingley. They attacked him in various ways—with barefaced questions, ingenious suppositions, and distant surmises, but he eluded the skill of them all, and they were at last obliged to accept the second-hand intelligence of their neighbour, Lady Lucas. Her report was highly favourable. Sir William had been delighted with him. He was quite young, wonderfully handsome, extremely agreeable, and, to crown the whole, he meant to be at the next assembly with a large party. Nothing could be more delightful! To be fond of dancing was a certain step towards falling in love, and very lively hopes of Mr Bingley’s heart were entertained.

“If I can but see one of my daughters happily settled at Netherfield,” said Mrs Bennet to her husband, “and all the others equally well married, I shall have nothing to wish for.”

Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility Persuasion

Persuasion Mansfield Park

Mansfield Park Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice Emma

Emma Persuasion (Dover Thrift Editions)

Persuasion (Dover Thrift Editions) Lady Susan

Lady Susan Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics)

Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics) Lady Susan, the Watsons, Sanditon

Lady Susan, the Watsons, Sanditon Darcy Swipes Left

Darcy Swipes Left Persuasion: Jane Austen (The Complete Works)

Persuasion: Jane Austen (The Complete Works) Mansfield Park (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Mansfield Park (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Sense and Sensibility (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Sense and Sensibility (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Sense and Sensibility

The Annotated Sense and Sensibility Pride and Prejudice (Clandestine Classics)

Pride and Prejudice (Clandestine Classics) Persuasion (AmazonClassics Edition)

Persuasion (AmazonClassics Edition) Persuasion (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Persuasion (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Complete Works of Jane Austen

Complete Works of Jane Austen The Watsons and Emma Watson

The Watsons and Emma Watson Northanger Abbey and Angels and Dragons

Northanger Abbey and Angels and Dragons Love and Friendship and Other Early Works

Love and Friendship and Other Early Works Emma (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Emma (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Sanditon

Sanditon Pride and Prejudice (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Pride and Prejudice (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Pride and Prejudice and Kitties

Pride and Prejudice and Kitties The Annotated Northanger Abbey

The Annotated Northanger Abbey Oxford World’s Classics

Oxford World’s Classics Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Persuasion

The Annotated Persuasion Emma (AmazonClassics Edition)

Emma (AmazonClassics Edition) The Annotated Emma

The Annotated Emma The Annotated Mansfield Park

The Annotated Mansfield Park The Annotated Pride and Prejudice

The Annotated Pride and Prejudice