- Home

- Jane Austen

The Annotated Sense and Sensibility

The Annotated Sense and Sensibility Read online

AN ANCHOR BOOKS ORIGINAL, MAY 2011

Copyright © 2011 by David M. Shapard

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Austen, Jane, 1775–1817.

[Sense and sensibility]

The annotated Sense and sensibility / by Jane Austen ; annotated and edited, with an introduction, by David M. Shapard.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95022-2

1. Young women—England—Fiction. 2. Sisters—England—Fiction. 3. Gentry—England—Fiction. 4. Inheritance and succession—Fiction. 5. Mate selection—Fiction. 6. Man-woman relationships—Fiction. 7. England—Social life and customs— 19th century—Fiction. 8. Austen, Jane, 1775–1817. Sense and sensibility. 9. Domestic fiction. I. Shapard, David M. II. Title.

PR4034.S4 2011a

823’.7—dc22

2011002249

Book design by Rebecca Aidlin

Maps by R. Bull

www.anchorbooks.com

v.3.1

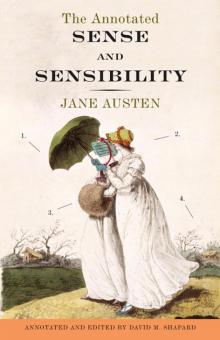

Cover illustration: Morning dresses by N. Heideloff and Gallery of Fashion, England, 1801 © V&A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Cover design by Megan Wilson.

A young woman reading a book outdoors.

[From The Repository of arts, literature, fashions, manufactures, &c, Vol. XIV (1815), p. 240]

[List of Illustrations]

Annotations to the Front Cover

1. Umbrellas for protection against inclement weather had been developed in the early eighteenth century, and by the end of the century were a standard accoutrement, especially among the wealthy. Of course, then as now, people did not always remember to carry them: one of the most important scenes in Sense and Sensibility occurs when one of the heroines, Marianne, is caught in a sudden rainstorm and tries to race home to escape it.

2. Walking outdoors was the principal form of exercise for ladies at this time, and Marianne is particularly devoted to it. The countryside where she lives and often takes walks with her sisters is mostly open and hilly, like the terrain depicted here.

3. Large muffs like this one were fashionable in this period; Marianne carries one when she ventures out during the winter.

4. The twisted, leafless trees and rustic hovels in the background were features admired by advocates of the picturesque, an influential aesthetic concept that is discussed by several of the main characters in the novel. Landscapes that were irregular, rugged, forlorn, or ruined in some way were considered to be particularly picturesque.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Annotations to the Front Cover

Illustrations

Notes to the Reader

Acknowledgments

Introduction

SENSE AND SENSIBILITY

VOLUME I

(Note: The following chapter headings are not found in the novel. They are added here by the editor to assist the reader.)

I The Dashwood Inheritance

II John and Fanny Dashwood

III Edward Ferrars

IV Edward and Elinor

V Departure from Norland

VI Arrival at Barton

VII First Dinner at the Middletons’

VIII Marianne on Colonel Brandon

IX Willoughby’s Rescue of Marianne

X Willoughby’s First Visit

XI Marianne and Willoughby

XII Willoughby’s Offer of a Horse

XIII Colonel Brandon’s Sudden Departure

XIV Willoughby’s Love of Dashwood Home

XV Willoughby’s Sudden Departure

XVI Arrival of Edward

XVII Edward’s Low Spirits

XVIII Edward and Marianne on the Picturesque

XIX Departure of Edward; Arrival of the Palmers

XX Mr. and Mrs. Palmer

XXI Arrival of the Miss Steeles

XXII Lucy Tells Elinor Her Secret

VOLUME II

I Elinor Reflects on Lucy’s Disclosure

II Elinor’s Second Exchange with Lucy

III Mrs. Jennings’s Invitation to London

IV Arrival in London

V Marianne’s Hopes for Willoughby

VI Encounter with Willoughby at Party

VII Willoughby’s Letter to Marianne

VIII Shocking News About Willoughby

IX Colonel Brandon’s History

X Arrival of the Miss Steeles in London

XI Elinor’s Encounter with John Dashwood

XII Dinner Party of John and Fanny

XIII Edward’s Encounter with Elinor and Lucy

XIV Fanny’s Invitation to the Miss Steeles

VOLUME III

I Revelation of Edward’s Engagement

II Edward Defies His Mother

III Colonel Brandon’s Gift to Edward

IV Edward Learns of Gift

V Elinor’s Visit to John and Fanny

VI Arrival at the Palmers’ House

VII Marianne’s Illness

VIII Elinor’s Conversation with Willoughby

IX Marianne’s Recovery

X Return to Barton

XI News of Lucy’s Marriage

XII Unexpected Arrival of Edward

XIII The Proposal

XIV Conclusion

Notes

Chronology

Bibliography

Maps

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Illustrations

A Woman with a Book Outdoors

A Satire on Sentimental Literature

A Grand Country House

A Glass and China Shop

A Barouche

A Girl Sketching

The Speaker of the House of Commons

Chawton Cottage

A Woman Reading

A Country House

A Picnic

Pheasant Shooting

A Pianoforte

A Gentleman

An Older Country House

Going Out Shooting

Foxhunting

Pointers

A Woman Reading Music

Selling a Horse

A Curricle

A Woman with Her Children

A Military Man

The Interior of a Stable

A Country House with a River

A Country House with a Park

A Drawing Room

A Woman Walking Outdoors

A Bookshop

A Print Shop

Picturesque Landscapes

Picturesque Landscapes

A Picturesque Traveler Sketching

A Picturesque Traveler Falling into the Water

A Gig

A Drawing or Writing Table

Hanover Square

The House of Commons

Two Fashionable Women

A Woman with a Sash

Two Women Looking at a Miniature

A Hot Water Jug and a Creamer

A Teapot

A Cup and Saucer

A Card Table

A Woman Receiving a Letter

A Chaise

Portman Square

A View of London

Carriages at an Inn

Mailing a Letter

A Woman Writing

The Wedgwood Shop in Londo

n

A London Outer Door

Grosvenor Square

A Woman with a Large Muff

A Sideboard

Women in Evening Dress

Postal Delivery

A Woman Holding a Letter

A Woman at a Table

A Chariot

A Bed

A Butcher

A Cherry Seller

A Scene in a Boarding School

A Landscaped Grounds with Water

A Country House with a Wall in Front

Pall Mall

A Man Being Arrested for Debt

A Public Coach

Bartlett’s Buildings

A Fashionable Young Man

Exeter Exchange

A Flower Garden

A Landscape with Trees Removed

A Coffeepot

A Woman with Sketching Pad

A Woman in Evening Dress

A Cottage

Plan for a Cottage

A Fashionable Mama

Contemporary Hats and Headdresses

Hyde Park

A London Church Service

A Bishop

A Dairymaid

A Woman Feeding Poultry

A View over Landscaped Grounds

A Modern Country House

A Classical Structure on Grounds

Playing Billiards

Two Women Outdoors

A Sofa

An Inner Doorway

Extravagant Living

Drury Lane Theatre

A Woman at the Opera

A Woman Reading a Large Book

The Ruins of an Abbey

Oxford

A Magnificent Cottage

Contemporary Wallpapers and Borders

Cows Grazing

A Marriage Ceremony

Notes to the Reader

The Annotated Sense and Sensibility contains several features that the reader should be aware of:

Literary interpretations: the comments on the techniques and themes of the novel, more than other types of entries, represent the personal views and interpretations of the editor. Such views have been carefully considered, but inevitably they will still provoke disagreement among some readers. I can only hope that even in those cases the opinions expressed provide useful food for thought.

Differences of meaning: many words then, like many words now, had multiple meanings. The meaning of a word that is given at any particular place is intended only to apply to the way the word is used there; it does not represent a complete definition of the word in the language of the time. Thus some words are defined differently at different points, while many words are defined only in certain places, since in other places they are used in ways that remain familiar today.

Repetitions: this book has been designed so it can be used as a reference. For this reason many entries refer the reader to other pages where more complete information about a topic exists. This, however, is not practical for definitions of words, so definitions of the same word are repeated at various appropriate points.

Acknowledgments

My principal expression of gratitude must go, as before, to my editor, Diana Secker Tesdell. She has proved an invaluable source of advice and assistance during every phase of the book; she has responded patiently to my numerous queries, has identified problems in what I submitted, has suggested better ways of expressing my thoughts, and has added her own plentiful insights into the novel. I am also grateful to Nicole Pedersen, as well as to others at Anchor Books, for the extensive efforts required for the preparation of such a complicated manuscript.

Additional thanks should go to the staff of the Bethlehem Public Library, the New York State Library, and the New York Public Library for helping me procure the materials essential for my research, with particular appreciation for the efforts of Gordon Noble at the first institution.

Finally, I must thank my mother and other members of my family for their continued encouragement and support in my endeavors.

Introduction

Sense and Sensibility was Jane Austen’s first published novel. Its appearance, in 1811 when she was thirty-five, marked the formal beginning of her literary career, but that career, and this novel itself, originated in much earlier, unpublished literary efforts.

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775, in Hampshire, a county in southern England. Her father, George Austen, was a clergyman and her mother, Cassandra Leigh Austen, whose father was also a clergyman, came from a family consisting principally of landed gentry; thus Jane Austen grew up among the social class she consistently depicts in her novels. The Austens were a large family of six boys and two girls, and they valued books and education. Her father supplemented his income by running a school for boys, and several of her brothers tried their hands at literary composition. The family also encouraged Jane’s literary efforts, the first surviving examples of which date to when she was thirteen. Her earliest writings were highly comical, and show the influence of other literary works of the time, many of which she satirized. As she matured, she wrote longer and more serious works, which reveal an increasing interest in the delineation of character.

One of these longer works was an early version of Sense and Sensibility. According to the later reminiscences of family members this early version, Elinor and Marianne, was written in the form of letters, a popular literary device of the time that she used for some of her other early writings. It was probably done in 1795, when she was nineteen.1 Late in 1796 she began First Impressions, which many years later became Pride and Prejudice. Her father sent the manuscript to a publisher, but it was rejected. Toward the end of 1797 she returned to Elinor and Marianne, modifying it and changing its name to Sense and Sensibility. She followed this with a new novel, Susan; it was also submitted to a publisher, who purchased the rights but never published it. Many years later it appeared, without significant modifications, as Northanger Abbey.

During this time Jane Austen continued to live with her parents and her sister, Cassandra, in her childhood home in Steventon, Hampshire. Her surviving letters indicate regular attendance at balls and other social events, and an interest in men, but no sustained romance or offer of marriage. The first known major event of her life occurred in 1801, when her father retired and moved the family to the popular spa and resort town of Bath. The family lived there, at various addresses, for the next four years. In 1805 Mr. Austen died, after which Mrs. Austen and her two daughters left Bath, settling eventually in Southampton, a port city in Hampshire. During this whole period Jane Austen did not complete any other novels, though she began at least one, the fragment called The Watsons. She also rejected, after briefly accepting, her one known offer of marriage. Finally, in 1809, she and her mother and sister were able to move into a cottage owned by her brother Edward in the quiet village of Chawton in Hampshire.

This new setting gave her the opportunity to devote herself more fully to writing. In 1810 she finished Sense and Sensibility; in October 1811 it appeared, though with a title page that simply said, “By a Lady.” It enjoyed modest sales, along with a couple of favorable reviews. January 1813 saw the publication of Pride and Prejudice, identified as “By the Author of ‘Sense and Sensibility.’ ” It experienced even greater success, and in 1814 and 1815 Mansfield Park and Emma, both completely new compositions, appeared. Unfortunately, in 1816 she grew increasingly ill; her ailment has not been identified for certain, though many have suggested it was what is now known as Addison’s disease, an endocrine disorder caused by a malfunction of the adrenal glands. She did manage during this period to finish one more novel, Persuasion, and to begin another, Sanditon. Eventually, however, she grew too weak to write, and on July 18, 1817, she died in the town of Winchester in Hampshire. Persuasion and Northanger Abbey were published later in the year, along with a brief biographical notice by her brother Henry that finally revealed her identity to the world.

Sense and Sensibility is in some ways the most didactic of all Jane Austen

’s novels. It is one of three whose titles consist of the names of abstract concepts, the others being Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion. This signals from the start that a moral message will be central to the story. But while the ideas that pride and prejudice are dangerous and that it is good to be somewhat but not too susceptible to persuasion are not particularly controversial, Sense and Sensibility engages in a contentious debate of its day and takes a stance at odds with a prominent cultural trend.

The term “sensibility” first appeared in English in the fifteenth century, used for either mental awareness or the power of sensation or perception. In the eighteenth century the term assumed additional meanings, and became more widely used. It came to denote a person’s general emotional consciousness or feelings, as well as, most significantly, a particular acuteness and sensitivity of feeling. This extra sensitivity could mean various things: among the feelings that were identified as especially strong in a person of sensibility were compassion for suffering and the unfortunate, empathy with others’ feelings, love of natural beauty, delicate artistic taste, and instinctive aversion toward immorality. Many argued that these qualities had become more pronounced in their own time, and that this signaled the progressive improvement and refinement of society. Sensibility was also believed by many to be more prevalent among the affluent and educated classes and among women. Much of the literature of sensibility emphasized the feminine nature of its qualities, and extolled women for being naturally more tender, delicate, emotional, and morally pure, especially when it came to sexual morality.

Important strains of eighteenth-century thought inspired and informed ideas of sensibility. One of these was the tendency among philosophers to explain human consciousness and knowledge as the product of sensations and experiences, rather than divine inspiration or rational deduction. Another, the theory of the moral sense, was an influential philosophical doctrine that explained morality as the product of an instinctive sense of benevolence in human beings. This sense allowed people to understand moral principles, served as proof of the validity of moral laws, and gave people a reason to act morally, since such actions would naturally produce pleasure while immoral actions would produce pain. Most of the major philosophers of the century advocated one or both of the above doctrines.

Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility Persuasion

Persuasion Mansfield Park

Mansfield Park Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice Emma

Emma Persuasion (Dover Thrift Editions)

Persuasion (Dover Thrift Editions) Lady Susan

Lady Susan Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics)

Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics) Lady Susan, the Watsons, Sanditon

Lady Susan, the Watsons, Sanditon Darcy Swipes Left

Darcy Swipes Left Persuasion: Jane Austen (The Complete Works)

Persuasion: Jane Austen (The Complete Works) Mansfield Park (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Mansfield Park (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Sense and Sensibility (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Sense and Sensibility (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Sense and Sensibility

The Annotated Sense and Sensibility Pride and Prejudice (Clandestine Classics)

Pride and Prejudice (Clandestine Classics) Persuasion (AmazonClassics Edition)

Persuasion (AmazonClassics Edition) Persuasion (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Persuasion (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Complete Works of Jane Austen

Complete Works of Jane Austen The Watsons and Emma Watson

The Watsons and Emma Watson Northanger Abbey and Angels and Dragons

Northanger Abbey and Angels and Dragons Love and Friendship and Other Early Works

Love and Friendship and Other Early Works Emma (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Emma (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Sanditon

Sanditon Pride and Prejudice (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Pride and Prejudice (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Pride and Prejudice and Kitties

Pride and Prejudice and Kitties The Annotated Northanger Abbey

The Annotated Northanger Abbey Oxford World’s Classics

Oxford World’s Classics Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Northanger Abbey (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Annotated Persuasion

The Annotated Persuasion Emma (AmazonClassics Edition)

Emma (AmazonClassics Edition) The Annotated Emma

The Annotated Emma The Annotated Mansfield Park

The Annotated Mansfield Park The Annotated Pride and Prejudice

The Annotated Pride and Prejudice